Harnessing the law for the public and the planet

Two chapters in a story of successful litigation

More than 100 successful cases

Litigation has been a tool in the The Public Interest Network toolkit since the early days of PIRG. In the 1980s, NJPIRG pioneered the use of citizen suit provisions to enforce the Clean Water Act — a strategy that the National Environmental Law Center, which we founded in 1990, expanded to great effect across the country. Together — NJPIRG and other PIRGs, NELC, our state environmental groups and Community Action Works — have filed more than 100 enforcement actions under the nation’s environmental laws. To date, each completed action has resulted in a court victory, a favorable settlement, or a commitment by the government to enforce the law.

More importantly, in each case, illegal pollution was curtailed. And the suits have resulted in more than $250 million in court-ordered penalties and facility upgrades, to both reduce pollution and help remediate environmental damage already done.

Video credit: BlackBoxGuild via Shutterstock

A recourse of last resort

Lawsuits are rarely our first choice. When it comes to social change, the more democratic the process, the more sustainable the progress. Change via legislation, passed by democratically elected representatives, thus is usually preferable to the making of “new law” by the courts.

But lawsuits are sometimes appropriate and necessary. When constitutional protections of individual rights are at stake, or when laws are being ignored by private parties or government officials (as was often the case during the Trump administration), the courts may be the only viable recourse.

Courts exist to make sure people, corporations and government itself obey the law. “Citizen lawsuit” provisions in some federal and state statutes give the people the power to enforce the law when the government doesn’t. In more than 100 cases, Public Interest Network groups have exercised that power, as illustrated in the stories that follow.

Video credit: BlackBoxGuild via Shutterstock

About this series: PIRG and The Public Interest Network have achieved much more than we can cover on this page. You can find more milestones here.

Of 3,000 violations, just 3 fines

The 1972 federal Clean Water Act set in motion a new system for protecting America’s waters. The government would set limits on pollution discharges. Companies would report their discharges. If they discharged more, say, benzene or heavy metals than their permits allowed, the government would impose a stiff fine and, if necessary, take away their permit.

By 1980, it was clear that the water in New Jersey was nowhere near achieving the law’s goal of being fishable and swimmable by 1983. An NJPIRG study pointed to a big factor in the failure: Of more than 3,000 documented clean water violations in the state, only 3% spurred any government action at all. The total number of cases resulting in fines? Three.

Yet the Clean Water Act itself offered a solution to the enforcement problem: When government fails to enforce the law, the Act grants citizens the right to sue polluters to compel action.

Creative solutions, a willingness to try them

In 1983, NJPIRG’s senior attorney, Ed Lloyd, led a team of lawyers in filing, on behalf of our members, our first 15 Clean Water Act citizen enforcement cases, against such companies as Monsanto for its illegal discharges into the Delaware River.

By 1985, NJPIRG Executive Director Ken Ward noted the opportunity the organization had to help make New Jersey a leader: “Our severe environmental problems are an incentive both for creative solutions and for a public willingness to try them out.”

Over the next decade, under Ken’s and Ed’s leadership, the number of successful NJPIRG citizen suits filed to enforce the Clean Water Act would rise to 53, including cases against Exxon, Chevron and Georgia-Pacific. In each case, court rulings or settlements among the parties resulted in a stop to illegal pollution and a payment of penalties -- totaling $32 million, much of which funded local environmental projects.

These cases broke new ground, including the first citizen suit under the Clean Water Act to result in a summary judgment (the Monsanto case), the first to uphold the constitutionality of the citizen suit provision of the Clean Water Act (Monsanto again), the first to win a preliminary injunction against further violations (a case against Top Notch Metal Finishing), and the first cases to impose the maximum penalty of $10,000 per violation (the Monsanto, Hercules and Powell Duffryn Terminals cases).

And the staff of the nation’s top law enforcement official — Attorney General Janet Reno — recognized NJPIRG for winning more of these cases than any other citizen group in the country.

The citizen enforcement model worked. And it would soon be replicated across the country.

Photo: U.S. EPA

NJPIRG streamwalkers protest illegal discharge at Morses Creek. Photo by staff

Ed Lloyd (NJPIRG Legal Counsel) files lawsuit against a water polluter. Photo by staff

NJPIRG’s Ken Ward. Photo by staff

A bad neighbor in Baytown, Texas

In 2004, Baytown, Texas, located about 25 miles from downtown Houston, was home to Sharon Sprayberry.

From her house, Sharon could see the towering flares of ExxonMobil’s Baytown refinery belching fire and smoke. Before long, Sharon developed respiratory problems. By 2012, the problems were so bad she had to move. She doesn’t even visit her old friends in Baytown anymore: the air is too hard to breathe.

10 million pounds of pollution

Sharon’s story is far from unique. Other Baytown families have moved out of fear of the air their children breathe, or hurried grandchildren indoors when the odors and haze are especially bad. That’s life when your neighbor is the largest oil and chemical refinery in the United States.

Every time Exxon’s facility burped fire or smoke, it also emitted dangerous air pollutants — and it did so on a frighteningly regular basis. Between October 2005 and September 2013, the Baytown facility unlawfully released more than 10 million pounds of carcinogens and respiratory irritants, vastly exceeding the limits permitted under the 1990 revisions to the Clean Air Act.

Like the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act contains a citizen enforcement clause. So, when government officials failed to stop ExxonMobil’s violations, Environment Texas put the citizen suit provision of the law to work. In 2010, the National Environmental Law Center (NELC) filed suit against ExxonMobil on behalf of Environment Texas and our members.

A David takes on a Goliath

Founded in 1990, NELC expanded on NJPIRG’s model for citizen-initiated legal action and took it nationwide. Headed by Litigation Director Chuck Caldart and Senior Attorney Josh Kratka, NELC’s legal actions have helped enforce the law against scores of polluters across the country. The ExxonMobil case would be the team’s biggest to date.

NELC and Environment Texas were taking on one of the most successful corporations in human history. Yet there was some precedent for hope. Prior to the Exxon suit, NELC suits against Shell Oil and Chevron Phillips had compelled those companies to curtail illegal discharges and pay penalties of $5.8 million and $2 million, respectively, for violations at their own Texas refineries. Yet when NELC served ExxonMobil with a notice of our intention to sue in 2009, the company made clear it was prepared to fight.

Here’s the thing, though: Exxon didn’t deny that it was polluting in excess of its operating permits. The emissions numbers cited by Environment Texas and NELC came from the company’s own self-reported metrics. Instead, Exxon argued that Baytown’s citizens had no right to sue in the first place.

In a legal battle that has lasted more than a decade, the courts have disagreed. Following a string of appeals, a federal judge announced that Exxon was responsible for 16,386 days of Clean Air Act violations and, in March 2021, levied a $14.25 million fine — the largest civil penalty ever imposed in a citizen-initiated Clean Air Act suit.

As of January 2022, Exxon has filed yet another appeal. And Baytown residents are still putting up with more pollution than they should have to tolerate. But NELC and Environment Texas aren’t backing down.

Photo credit: Anatoliy Gleb via Shutterstock

Environment Texas Director Luke Metzger announces the lawsuit with attorney Philip Hilder, attorney David Nicholas and Sierra Club’s Brandt Mannchen. Photo by Photo Denbow

NELC Senior Attorney Josh Kratka presented arguments at the ExxonMobil trial. By staff

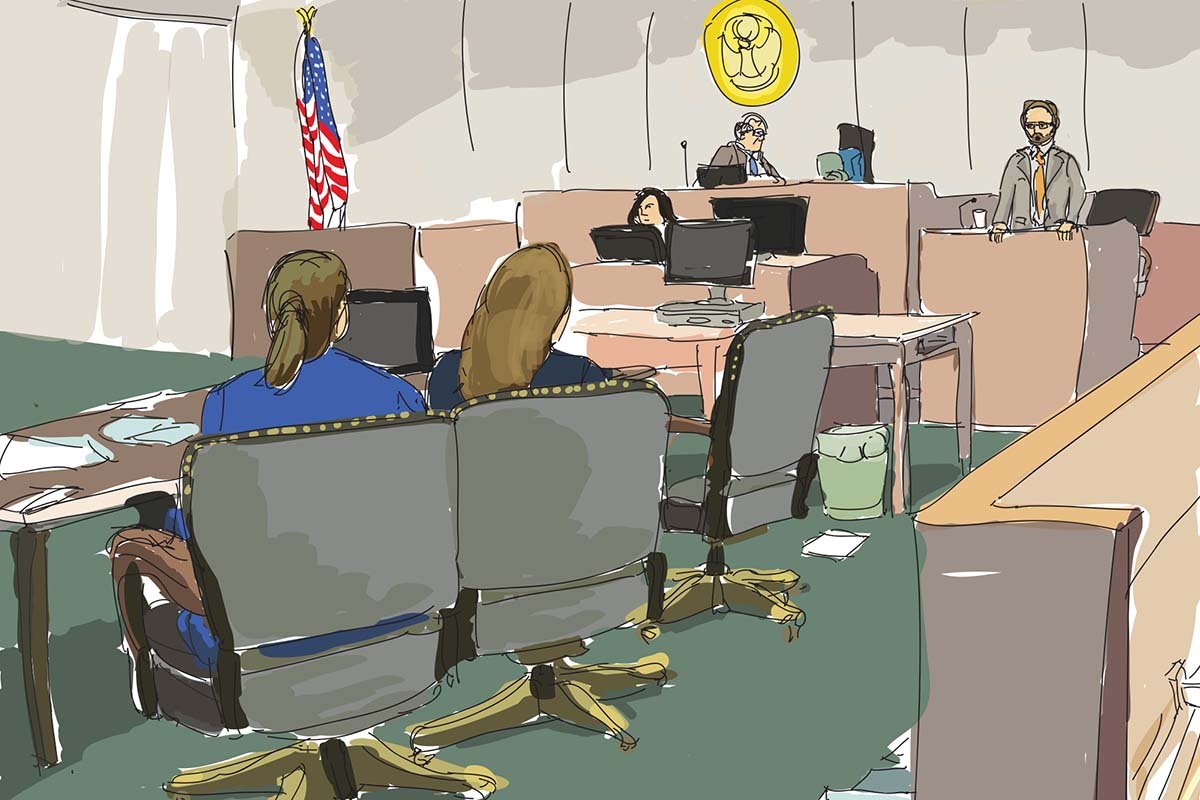

Courtroom sketch of Luke Metzger testifying in court against ExxonMobil. By staff