Preventing more toxic tragedies

Three efforts to safeguard our health and environment against toxic threats

Cautionary tales

In the 1970s and 80s, the names of certain places — Love Canal in New York, Woburn in Massachusetts, Bhopal in India — became shorthand references to cautionary tales of toxic contamination, environmental disease and deaths, including those of children.

By then, the development of tens of thousands of new chemicals had, in many ways, made life more comfortable, convenient and even safer in certain instances. Yet along the way, few people had stopped to ask whether these chemicals were (if they were necessary at all) being used, stored, transported and disposed of in ways that protected public health and safety. They weren’t, and the tragic consequences became more apparent with each new headline about the latest toxic disaster.

Better safe than sorry

PIRG helped expose these dangers through investigative reports, public education and advocacy. While our initial work focused on the need for cleaning up the worst toxic spills and dumpsites, we increasingly adopted an approach rooted in the precautionary principle.

If the unbridled use of toxic chemicals throughout society ever made sense, its logic falls apart as society achieves greater material wealth and abundance while the evidence accrues of lives lost and damaged. The burden of proof for whether it is wise to risk public exposure to a toxic chemical should no longer rest with the victims or potential victims. From the 1980s on, our staff and members won new laws and policies that gave communities the right to know what chemicals were entering their air, water and land; called on industries to reduce their use of toxic chemicals in favor of safer substitutes; and phased out or outright banned toxic substances that posed too great a risk for too little benefit. Here are three of these stories.

Banner credit: Public Domain

A disaster in India amplifies a warning

Some time during the night of Dec. 2, 1984, an estimated 93,000 pounds of methyl isocyanate and other toxic gases escape from a Union Carbide chemical plant in Bhopal, India. By the next morning, several thousand people in nearby communities lose their lives after they choke on the gas and their lungs and hearts fail. More than 500,000 people are exposed.

Suddenly, questions that Americans have been asking about the chemical facilities and dumpsites near their own homes take on greater urgency: Could what happened in Bhopal happen here?

Within two years, Congress delivers a response: a stronger federal hazardous waste “Superfund” law, with new requirements that companies disclose their toxic chemical emissions — an amendment that passes by a slim margin, thanks in part to U.S. PIRG advocacy and action.

A tragedy in NY spurs action

The original Superfund law, passed in 1980, was a response to “one of the most appalling environmental tragedies in American history.” As The New York Times reported on August 1, 1978:

Twenty five years after the Hooker Chemical Company stopped using the Love Canal [in upstate New York] as an industrial dump, 82 different compounds, 11 of them suspected carcinogens, have been percolating upward through the soil, their drum containers rotting and leaching their contents into the backyards and basements of 100 homes and a public school built on the banks of the canal.

Children returned from play at school and in their yards with burns on their hands. Miscarriages and birth defects increased. After Lois Gibbs, a Love Canal resident and mother of a young child, organized her neighbors and demanded action, New York Gov. Hugh Carey announced on Aug. 7 that the state would purchase the residents’ homes. Two years later, President Jimmy Carter signed into law the federal Superfund program, designed to clean up the nation’s worst hazardous waste sites. Yet even with an original outlay of $1.6 billion to cover costs at sites where the polluting company couldn't pay for cleanup, the Superfund fell short.

Yet even with an original outlay of $1.6 billion, the Superfund couldn’t cover the cleanup costs for all sites. To fill the gap, state PIRGs advocated and organized for state Superfunds, winning approval in New York, Massachusetts, Missouri, Vermont and Colorado in the early 1980s.

A federal test is passed

Meanwhile, in 1983 the state PIRGs had united to form U.S. PIRG, our federal advocacy office in Washington, D.C. As Congress began debate on whether and how to reauthorize the Superfund program, Rick Hind, U.S. PIRG’s first environmental advocate, led a campaign that sought to combine the “inside game” of direct lobbying in the Capitol with the “outside game” of PIRG’s presence and grassroots action in the states.

The debate in Congress presented PIRG and other environmental champions with three major challenges: Could we win congressional approval for 1) a significant boost in toxic waste cleanup, 2) a tough requirement that polluters pay a greater share of the cost, and 3) a new “right to know” program compelling companies to disclose their toxic emissions?

These victories built momentum for the first ever state PIRG federal victory: the 1986 reauthorization of the hazardous waste Superfund law and the Toxics Release Inventory. This effort was headed by Rick Hind.

On October 17, 1986, despite earlier threats to veto the law, Reagan signs, includes $8.5 billion for cleanup, with more than a third of the funds coming from new taxes on oil and chemicals.

And even after this landmark victory, state PIRGs continued to prod for more local action. In 1987, for example, after a toxic cleanup bill stalled in the Legislature, WashPIRG and a coalition of groups put Initiative 97 on the ballot. The tough cleanup measure won approval from 56% of the voters.

Photo: Love Canal cleanup. U.S. Department of Justice

WashPIRG Director Wendy Wendlandt led the organization’s campaign for I-97, the initiative that created what a state official later hailed as the nation’s most successful toxic cleanup program. Photo by staff

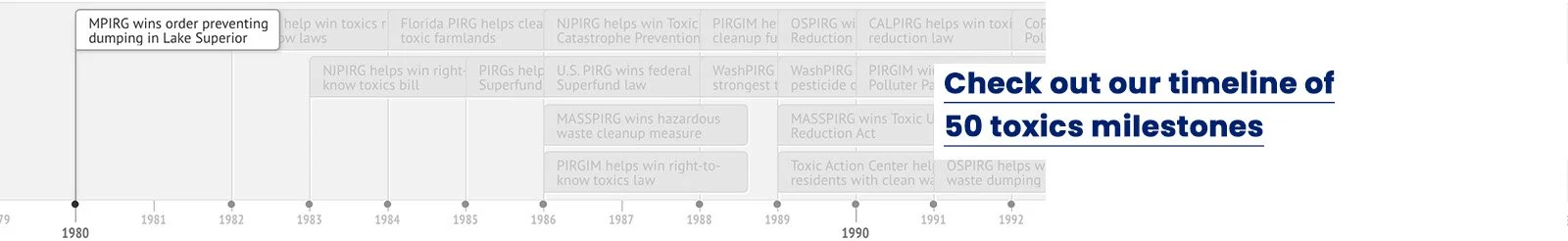

Voter support for a sweeping, MASSPIRG-backed 1986 hazardous waste cleanup proposal helped pave the way for the Toxics Use Reduction Act. Here, MASSPIRG’s Mindy Lubber speaks to the press about the 1986 ballot initiative, which won 74% of the popular vote. Photo by staff

U.S. PIRG, the Washington, D.C. lobbying office for the state PIRGs, celebrated its third year with victories on the Superfund and the Safe Drinking Water Act. Here, lobbyists Rick Hind (left), Michael Caudell-Feagn (center) and Pam Gilbert talk in front of the U.S. Capitol. Photo by staff

Wells contaminated, lives lost in Woburn

In December 1979, leukemia cases are spiking in Woburn, a town northwest of Boston.

Tests find that two public wells are contaminated with trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene (PCE) and other industrial pollutants. Eventually, eight children die and others fall ill. On May 14, 1982, residents file suit against W.R. Grace, a chemical company, and Beatrice Foods, which owns the site where plaintiffs allege the contamination originated. In 1986, the companies settle — years too late for the families who lost their kids.

A big win and a new challenge

Woburn was not alone. The number of known hazardous waste sites in Massachusetts had grown from 60 in 1983 to 118 in 1985. A MASSPIRG analysis estimated the true number was likely in the thousands.

In 1986, MASSPIRG spearheaded a campaign that won voter approval — by a record margin — of a ballot initiative to speed the investigation and cleanup of toxic sites. The vote was a win for public health and a signal that the organization had the wherewithal to put even stronger proposals on the ballot.

Since 1983, MASSPIRG’s Bill Ryan had been crafting an approach that could reduce the generation of hazardous waste: cutting the use of toxic chemicals in the first place and therefore minimizing the threat posed by spills and other exposures to the environment, workers and families like those in Woburn.

The Toxics Use Reduction Act

In 1989, after the release of a series of MASSPIRG reports, combined with advocacy and grassroots action, the Toxics Use Reduction Act was ready for prime time. Legislative leaders convened a series of meetings between environmental advocates and industry representatives to hammer out a compromise.

“We knew right away what the most contentious issues were,” said Margie Alt, who represented MASSPIRG. Among those issues were proposed phase-outs of the most dangerous chemicals — provisions that MASSPIRG strongly backed, but agreed to drop in exchange for industry support.

“Although we gave up these proposals in the negotiations, by staking out this territory and having the threat of a ballot initiative in the background, we were able to compromise, yet still end up with a strong law,” said Bill Ryan.

Gov. Mike Dukakis signed the Toxics Use Reduction Act into law on July 24, 1989.

Passage represented a landmark achievement. For the first time, industries were required to publicly disclose their use of toxic chemicals and plan for future reductions.

And it worked.

In the first 10 years after the law passed, industries covered by the law reduced their use of toxics by 40% and their production of toxic waste by 58%, exceeding the law’s promise of cutting toxic waste in half. By 2019, toxic chemical use in Massachusetts had dropped from 1.2 billion pounds per year in 1990 to 0.7 billion pounds.

The law not only reduced toxic emissions; it also led to the creation of the Toxics Use Reduction Institute at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, and it has been recognized as an innovative and effective model for state environmental policy. The measure also served as a model for similar proposals later adopted following PIRG campaigns in New Jersey and Oregon.

Photo credit: John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

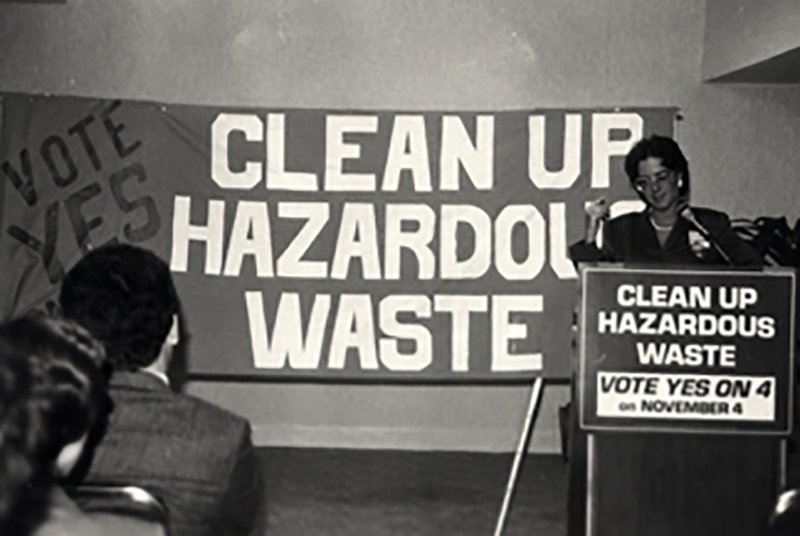

Hazardous waste program director Bill Ryan releases a 1983 MASSPIRG report on the effects of toxic dumping on drinking water. Ryan was the chief architect of MASSPIRG’s cutting-edge toxics use reduction proposal, which was enacted in 1989. Photo by staff

When Gov. Michael Dukakis (right) signed the Toxics Use Reduction Act, he invited MASSPIRG’s Margie Alt, chief advocate for the bill, to speak. Photo by staff

NJPIRG’s Rob Stuart (center) meets with state Rep. Byron Baer and Gov. Tom Kean about toxics issues in New Jersey, 1986. Photo by staff

Losing the farm to PFAS

On a spring day in 2016, Susan Gordon receives devastating news: The water at the 200-acre farm she and her husband manage near Colorado Springs is contaminated.

Less than 10 miles away, the Peterson Air Force Base has been using firefighting foam in training exercises for decades. The foam contains chemicals that persist so long in the environment they’re nicknamed “forever chemicals.” More formally known as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), the pollutants are linked to liver problems, asthma, kidney and testicular cancer, obesity, immune disorders, thyroid disease and Type 2 diabetes.

In December 2017, Susan and her family shut down their farm. “Everything just stopped,” she said. “To have it so abruptly ended was hard. We just felt so helpless.”

Over the next few years, Susan and other people affected by PFAS, with help from groups such as Community Action Works and PIRG, raised awareness of these forever chemicals — and won some small first steps toward cleaning them up and preventing further exposures.

Awareness grows as PFAS are found everywhere

In recent years, PFAS contamination has been found everywhere — including, according to the CDC, in the blood of nearly everyone tested for the chemicals.

And it’s no wonder. The substances are used in a wide range of everyday products to make them non-stick (as in cookware), stain-resistant (carpets), waterproof (clothing), and grease-proof (food packaging).

Researchers estimate that PFAS can be found in the drinking water supplies for over 200 million Americans.

As evidence of the contamination has spread, so too has awareness, with help from our advocates and organizers. In October 2020, in Fairfield, Maine, Lawrence and Penny Higgins heard their neighbors were having their water tested for PFAS.

Given that compost containing PFAS-contaminated sludge had been spread on nearby farmland, Lawrence and Penny decided to do the same. When the tests came back, state officials advised the couple to stop drinking their water, using it for cooking, and giving it to their animals. With help from Community Action Works, Lawrence organized a Facebook group of over 200 people who are now calling on officials to test every well, provide clean water to all families, and end the use of contaminated sludge in compost.

Targeting PFAS use in firefighting, food packaging and more

PIRG advocates have called for legislative action in Congress and in state capitols, as well as more responsible practices by corporations.

In 2019, Congress approved a PIRG-backed provision to phase out the military’s use of PFAS in firefighting foam. On July 21, 2021, the U.S. House approved the bipartisan PFAS Action Act, directing the EPA to limit PFAS discharges into waterways and call a moratorium on new PFAS chemicals.

PIRG also has urged companies such as McDonald’s and Burger King to stop their use of PFAS in food packaging and REI to phase out the sale of outdoor clothing and gear that uses PFAS.

Photo credit: Irina Kozorog via Shutterstock

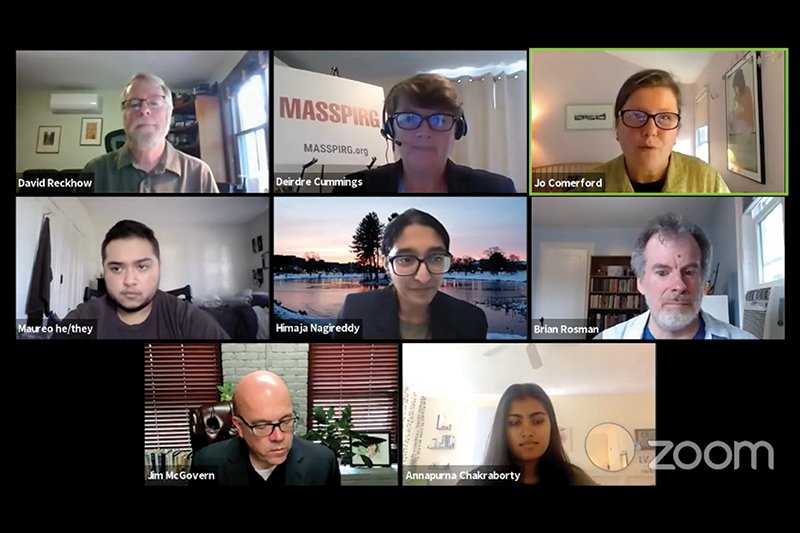

MASSPIRG’s Legislative Director, Deirdre Cummings speaks with U.S. Rep. Jim McGovern (MA-2), state Sen. Jo Comerford and her office’s legislative director Brian Rossman, Harvard University Presidential Public Service Fellow Himaja Nagireddy, environmental engineering professor Dr. David Reckhow, Clean Water Action Associate Director Maureo Fernández y Mora, and other experts and advocates about the importance of protecting Bay Staters from toxic PFAS “forever chemicals.” Image by MASSPIRG

“Is it really worth risking our health so our hands don’t get greasy?” asks asks U.S. PIRG’s Danielle Melgar. Photo by staff

Farmer Susan Gordon speaks to us about her experience with PFAS contamination. Click the image to watch a video of Susan’s story. Image by Eugene Parechyn