Students as citizens

Three chapters in the story of the Student PIRGs

A civic experience for students across America

At a time when higher education is increasingly seen as a tool for producing bigger earners, not better people, the Student PIRGs continue to extol the importance of democratic engagement and enhance the civic experience of students across America.

The work of PIRG students takes place not in a classroom or laboratory, but in the real world with real stakes, creating unique opportunities for “experiential learning.” Challenging predatory on-campus marketing practices by credit card companies or finding a path for a university to generate 100% of its energy from renewable sources are anything but academic exercises. Instead, these projects give students a taste of what it means to be an effective agent for change in the world outside the university.

Campaigns relevant to each new generation

Often, PIRG students find that the changes they seek can only be achieved through the political system. In recent years, PIRG students have chosen to campaign for renewable energy, a reduction in single-use plastics, and an end to the overuse of antibiotics in agribusiness—all issues with special relevance to a generation growing up amid a warming planet, oceans at risk, and increasing concern about the impact of our food system on our environment and our health.

By engaging with the political system on pressing issues, PIRG campaigns provide students with a view of how power and politics work in the real world—a depiction that isn’t always captured by civics textbooks or in the media.

Five decades after the first PIRG organizing drive at the University of Oregon, PIRG chapters continue to train students in the tools of effective citizenship and provide real-life opportunities to put those tools to work for a better world. Here are three chapters that tell part of the story of PIRG’s campus-based action for a change.

About this series: PIRG and The Public Interest Network have achieved much more than we can cover on this page. You can find more milestones here.

We’re gonna need a bigger room

It’s 1970. Many college students are looking for new ways to make a difference in the lives of Americans who are still at war in Vietnam and at odds with each other over the war and many other issues.

At the University of Oregon in Eugene, Ralph Nader, the crusading attorney, has just finished a well-attended lecture. Nader, along with his young associates Donald Ross and Jim Welch, has planned a smaller meeting to follow the lecture to discuss a new idea: adapting Nader’s unique brand of advocacy for college campuses. by forming a student-directed, student-funded public interest research group.

They book a room that night that holds 150 people. But they’re certain they won’t fill it, not late on a Friday night on a raucous college campus.

They’re proven wrong when 500 students show up.

Within a year, state college and university officials have approved the creation of the Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group (OSPIRG) at all seven of of the system’s campuses. So begins a model of campus-based social action that will last for 50 more years (and counting) and be adopted by students at dozens of other colleges and universities in Minnesota, Massachusetts, New York, California, Missouri and other states across the country.

Checking prices, walking streams, uncovering shady practices

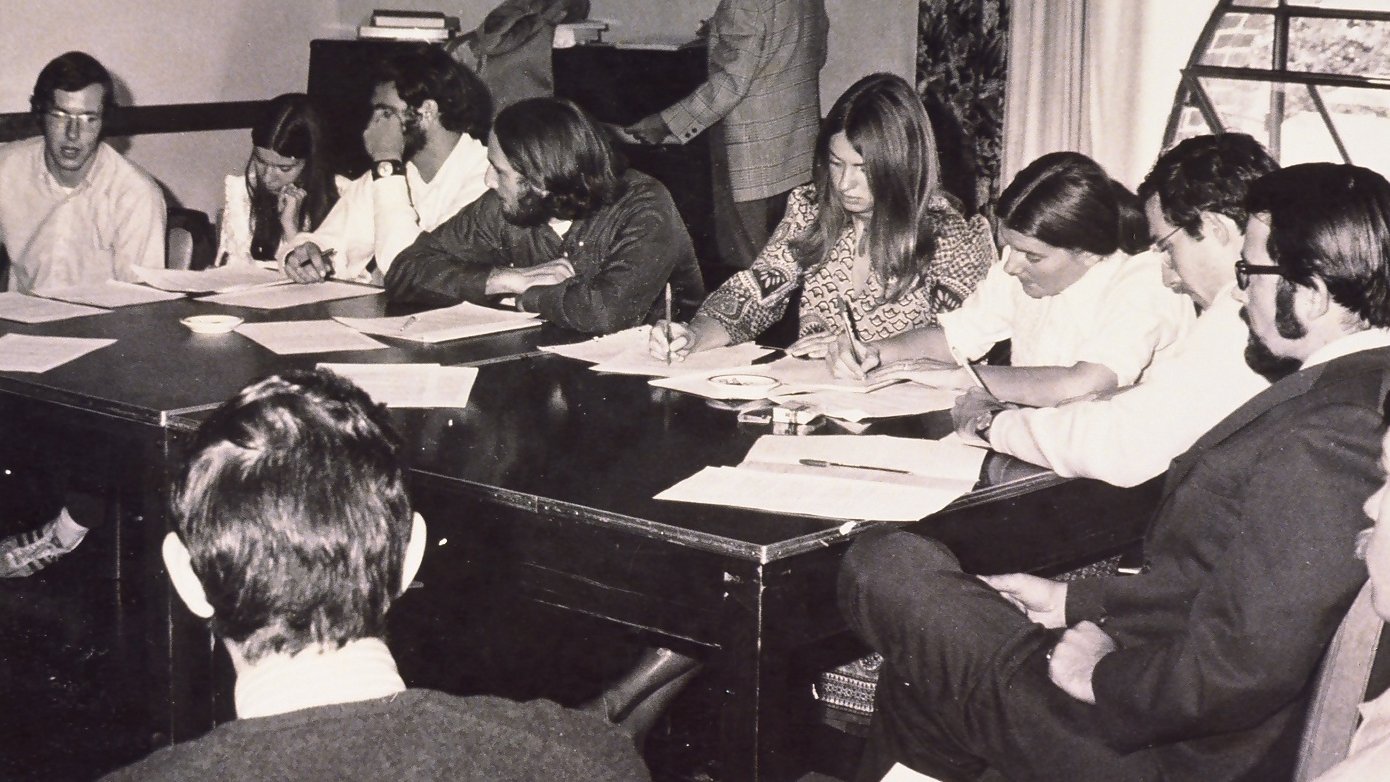

From the beginning, student involvement in PIRG chapters takes many forms.

In Oregon, PIRG student volunteers bring cars in good condition to local garages and reveal which crooked shops tell the students they need phantom repairs. In California, PIRG students conduct price surveys at local grocery stores and publicize the results (an especially helpful tool for shoppers in the days before the internet).

In New Jersey, student Streamwalkers don hip waders and check pollution discharges against state permits. By 1980, NJPIRG has more people monitoring the state’s rivers and streams than all of New Jersey’s public agencies combined.

In 1975, CALPIRG volunteer and law student George Schultz’s investigations help expose a major price-fixing scandal within the state’s beef industry. Schultz’s project involves undercover industry contacts dubbed “meat throats,” the theft of case files from our lawyer’s office, testimony before Congress, a class-action lawsuit, an appearance on “60 Minutes,” and, in a victory for consumers, 13 convictions in the industry.

As the years go by, tens of thousands of student PIRG volunteers conduct more research and investigations, compile and release reports and consumer guides, set up consumer hotlines, earn attention in the news media, lobby public officials, collect signatures on initiative and other petitions, speak with community groups, organize service projects to help the hungry and homeless, and much more. Given the educational value of many of these projects, thousands of students earn course credit as they learn the skills and value of civic engagement.

Special interests push back

Whenever some people push for social change, other people push back.

In 1979, College Republicans sue New Jersey PIRG chapters at Rutgers University, over its funding by student fees — even though students approved the creation of the PIRG fee in a campus-wide vote. The suit, as well as similar legal challenges, fails.

In 1995, legislation is filed in Congress to prohibit federal funding for colleges that employ the funding system used by many student PIRGs. Dubbing the provision the “campus gag rule,” PIRG students and organizers successfully persuade Congress to defeat the measure as an infringement of students’ rights to free speech and free assembly.

Ralph Nader speaks with MoPIRG activists in 1974. Photo by staff

NJPIRG Streamwalkers test water quality. Image from a documentary about PIRG created by the Center for Study of Responsive Law

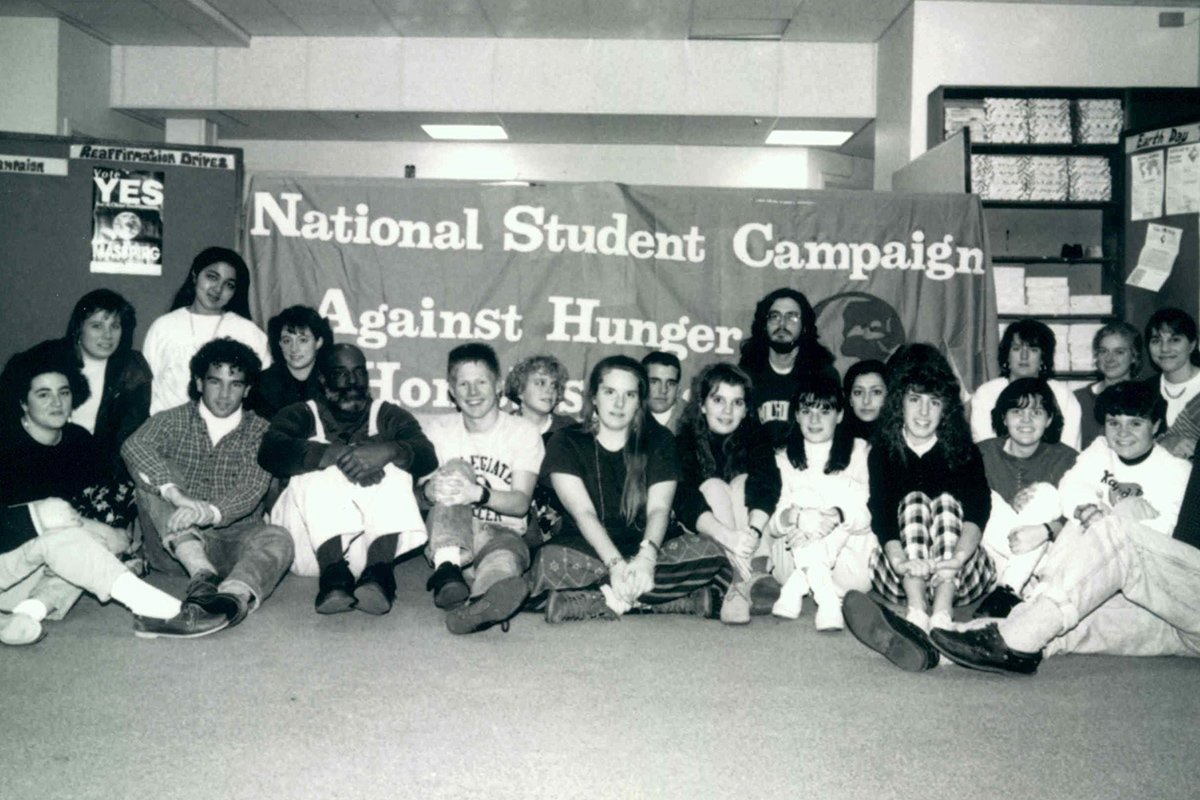

Student volunteers with the National Student Campaign Against Hunger and Homelessness. By staff

Organizing through a pandemic

In the late winter of 2020, Manny Rin, the director of Student PIRGs’ New Voters Project, is on a plane traveling home from Atlanta, where he has just led a training for student leaders to prepare them to run voter registration drives for the upcoming election.

Weeks later, Manny’s plans change. The president has declared a state of emergency, much of the country and nearly every college campus is shut down. Interest in the November election is high, but nobody knows how fear of COVID-19, social distancing guidelines and shifting election rules will affect voter turnout, especially among younger voters.

As the election draws near, more than 5,000 students in 15 states take part — virtually — in the PIRG New Voters Project, contacting nearly 400,000 other students and urging them to get out and vote. This effort contributes to an eye-popping increase in young voter participation, with youth turnout up 22% over 2016 in New Jersey, 18% in Arizona, 17% in California and 14% in Georgia.

“Of course, some of 2020’s historic turnout can be attributed to expanded vote by mail options and increased interest in the election,” said Manny. “But this rise is also the culmination of years of our program investing in training young activists on college campuses and running a peer-to-peer voter engagement program at the local level.”

America’s largest nonpartisan young voter project

Voter registration drives had long been on the menu of public interest projects at Student PIRG chapters.

In 1984, these efforts scale up in a big way. Beth DeGrasse and other PIRG staff team up with Daniel Malarkey and other student leaders to organize a major conference on the student vote. They enlist 880 campus leaders and newspaper editors to call on students across the country to attend a conference on student voter registration. Over the weekend of Feb. 11-13, 1,500 students from 42 states come to Harvard University to hear civil rights leader Jesse Jackson and other speakers, engage in workshops and conversations, and launch the National Student Campaign for Voter Registration.

That year, Jackson is also running for president. Given his campaign schedule, the civil rights leader admits to the students he had hoped for a low turnout at the conference, so he could cancel and concentrate his energies on the Iowa caucuses.

“But here you are,” he says to a packed Memorial Hall while hundreds of others watch on closed-circuit TV because they can’t fit inside the room. With a sly smile he adds, “Something must be going on.”

Indeed, something is going on: Over the next eight-plus months, the campaign becomes the most successful student voter registration effort in the nation’s history, reaching 1,000 campuses and 2,000 communities, involving 10,000 volunteers, and helping 750,000 new young voters register (a 17% increase), while adding another 100,000 new registrations in predominantly low-income and minority communities.

Tactics evolve, the goal remains the same

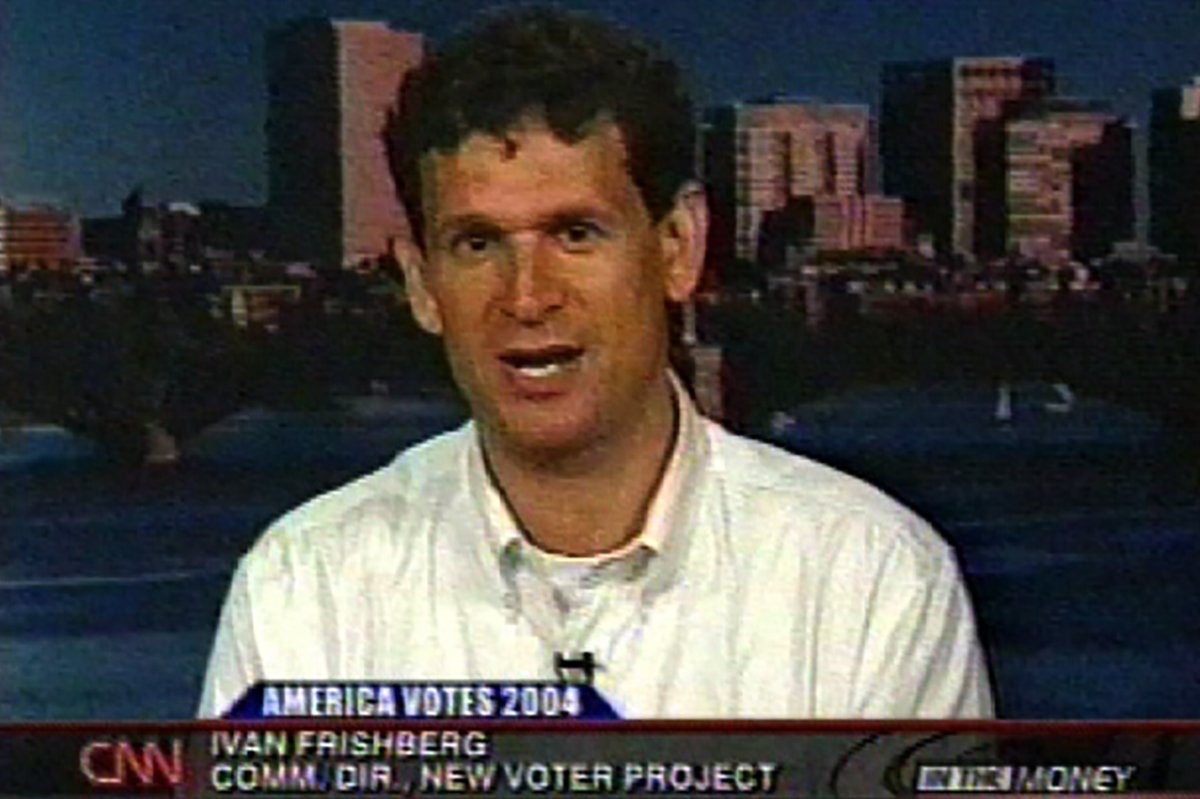

In 1994, the Student PIRGs team up with Rock the Vote!, United States Student Association, National Council of La Raza and others to form the Youth Vote coalition. In 2004, the Student PIRGs rename NSCVR to become the (much pithier) New Voters Project and the project expands thanks in part to a major grant by the Pew Charitable Trusts, secured under the leadership of PIRG’s Ivan Frishberg. As technology and students’ preferred modes of communication evolve, Manny Rin, Leigh-Anne Cole and other PIRG organizers incorporate social media, text and other types of peer-to-peer organizing, informed by sophisticated research conducted by partners such as the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE).

By 2020, the project is now America’s oldest and largest youth voter mobilization program, helping more than 2 million young people register and vote in elections spanning four decades.

Photo: Eckerd College / Angelique Herring

Ivan Frishberg leads the New Voters Project in 2004. Image from CNN news coverage.

Beth Degrasse speaks at the National Student Conference on Voter Registration in 1984. Photo by staff.

Manny Rin, the director of Student PIRGs’ New Voters Project, trains new organizers. Photo by staff

Money for nothing

You may remember the feeling: You sign up for a course you’re really excited to take. Then you look at the syllabus: The textbook costs $100. Or maybe $200 or $300. If you’re a more recent college grad, you may remember a course’s online materials being locked behind an expensive paywall. Or having to pay extra for “recommended” supplemental materials.

The irony is the textbook contains hardly any new content: only enough to “justify” the hefty price of a new edition.

Enter the Student PIRGs. Decades ago, PIRG student volunteers and interns organized book exchanges, allowing students to buy and sell their used textbooks. Over time, students begin to advocate more innovative solutions, including Open Educational Resources (OERs) — open-license learning materials freely available on the web.

Exposing publishers’ unfair publishing practices

Pearson, Cengage, Wiley, McGraw-Hill. Students know these major textbook publishing companies all too well. These four firms alone control more than 80% of the market.

The lack of competition allows the publishers to get away with a number of unreasonable price-hiking practices, including:

Publishing new editions of their textbooks every few years, even for subjects such as calculus and history, where the material is well-established and new editions differ little from past publications.

Bundling textbooks with access codes for supplemental online materials. This diminishes the resale value of the book itself once the access code expires.

Pushing “automatic billing,” whereby students are automatically charged on their tuition bill for course materials, with no easy way to opt out or shop around for cheaper alternatives.

It’s no wonder that, over 40 years the price of textbooks increases three times faster than inflation.

Toward free and open textbooks

These prices keep rising even as people can access nearly the sum total of human knowledge instantly on the internet — a fact that makes “open textbooks” a new opportunity to make prices more reasonable .

Open textbooks turn the traditional publishing model on its head. In direct contrast to traditional publishers that strictly control every facet of access and use of their textbooks and materials, open textbooks are available for free online, are free to download, and are affordable in print. Open textbooks and all OER material are published under an “open” license, allowing free and unfettered public use.

In 2003, PIRG students begin to persuade administrators to spend money and time to train and incentivize faculty to adopt open textbooks and other openly licensed materials for their classroom teaching. Starting at the University of California at Irvine, PIRG chapters bring the campaign to UMass Amherst, the University of Maryland, and Rutgers University, among other schools, winning approval for programs that save students millions of dollars.

Dave Rosenfeld helps put the campaign on the national stage. In 2007, Dave is the national program director for the Student PIRGs when a comprehensive federal report confirms the research on barriers to textbook affordability that he and the Student PIRGs had been conducting for years.

In 2011, student organizer Nicole Allen coordinates a “textbook rebellion” at Indiana University. Students are eager to stop and sign Nicole’s petition protesting high textbook fees — and the event helps drive the adoption of e-textbooks in more classrooms across the IU campus.

The Student PIRGs’ Make Textbooks Affordable campaign keeps winning: Convincing Congress to launch a pilot program that could save students $50 million per year; working with a coalition of student government leaders to get the U.S. Department of Justice to block a merger between two leading textbook publishers; and helping campuses across the country implement “course marking,” which allows students to see the full cost of all the materials for their classes before signing up.

Amplifying the student voice

As students speak up for open textbooks, the Student PIRGs also promote other solutions to control the cost of higher education. In 2018, for example, our #PellRaiser campaign helps stop congressional cuts to the Pell Grant program, which provides tuition assistance to millions of students every year.

The Student PIRGs’ Dave Rosenfeld. By staff

Photo petitions from students supportive of our textbooks campaign. By staff

The Student PIRGs’ Nicole Allen talks with a student about our Open Textbooks campaign. By staff