A more perfect union

Stories about making democracy work better

A tenuous experiment

The American experiment in democratic self-government has always been tenuous.

Flawed from the beginning – brutally, tragically so, in the case of slavery – American democracy also has contained within it the seeds of its own renewal.

From the stain of slavery to the exclusion of women, from the corrupting influence of “monied interests” to the struggle for civil rights, in each epoch of our country’s history, Americans have faced again and again the question of whether we could summon the will and the wisdom to achieve a more perfect union.

So far, the answer has been “yes,” thanks to the sweat, tears and too often the blood of countless American advocates and activists.

Challenges old and new

Yet nearly 250 years after we declared our country’s political independence, the strength and sustainability of our democracy is still more tenuous than any of us would like, bedeviled by attempts to resurrect barriers to voting, court decisions that prevent checks on special interest money, a civic culture frayed by extreme polarization, the declining faith in government, and an erosion of democratic norms – including the cornerstone concept of the peaceful transfer of power.

Once again, whether American democracy will flourish or fail depends in large part on advocates and activists for reform.

The staff and members of PIRG have done our part to meet many of these challenges over the past 50 years. We’ve won changes making it easier to register to vote, run drives to encourage students and other underrepresented constituencies to register and vote, and championed creative checks on the influence of corporations and the wealthy over our elections. Here are three stories of our work to sustain and strengthen our democracy.

A burdensome system

Not all that long ago, registering to vote in Colorado was no picnic.

To register, you had to visit a county clerk’s office that often opened at 9 a.m. and closed at 5 p.m. — meaning, if you had a 9 to 5 job, you had to take time off from work in order to register. The registration period closed more than a month before each election — an earlier deadline than you’d face in all but one other state. And clerks had the power to “purge” you from the list if you failed to vote in just a single general election.

These rules served to depress voter participation. But rules, of course, can be changed.

A modern solution

CoPIRG’s first attempts to persuade state lawmakers to reform the voter registration process met with no success.

Then, in 1982 Arizona enacted the nation’s first “Motor Voter” law. The idea was a simple update to reflect modern lives: People had to visit a state office when they applied for or renewed their licenses to drive. Why not allow them to register to vote at the same time? Especially since state registry offices already must verify their identities and places of residence?

It was a sensible idea, but the Colorado Legislature still failed to adopt Motor Voter. So CoPIRG and our allies decided to bring the issue to the voters via the ballot initiative process. Under the umbrella of Vote Colorado — a coalition that included CoPIRG, Common Cause, the state AFL-CIO, environmentalists, good government groups and other citizen organizations — we sent 300 volunteers across the state to collect the 47,000 signatures needed to put the proposal on the 1984 ballot.

In November of that year, with support from most of the state’s major newspapers and little organized opposition, the Motor Voter initiative was approved with 61% of the vote. The law would not only make it easier for citizens to register to vote, but would also limit election officials’ ability to remove voters from the rolls for missing an election.

Registrations jump to 82%

Motor Voter made a near-immediate difference. In the program’s first year, 175,000 people across the state registered to vote in motor vehicle bureau offices. By 1988, the percentage of eligible voters registered in Colorado rose to 82%, up from 59% in 1984. By 2021, the number of voters registering in vehicle registry offices was up to 250,000.

Then-CoPIRG director Tina Fahnenstiel-Zihlman, who led the coalition effort, emphasized how the Motor Voter effort also set a precedent for future initiative campaigns. “Up until Motor Voter, there was a period where no citizen initiatives passed. Motor Voter opened the door for citizen groups to win initiatives.”

The Colorado initiative also built momentum for Motor Voter proposals nationwide. In May 1993, President Bill Clinton signed the PIRG-backed national Motor Voter bill into law, allowing citizens to register to vote at government offices and, for the first time ever, through the mail. In the law’s first year, more than 30 million Americans used these provisions to register or update their voting information.

Photo: nyker via Shutterstock

Katie Reinisch CoPIRG organizer Katie Reinisch (right) joins Denver Mayor Federico Peña (center) at a Community Voter Registration Day event. By staff

President Clinton signs the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, also known as the Motor Voter Act, May 20, 1993. Photo courtesy; William J. Clinton Presidential Library

Organizing through a pandemic

In the late winter of 2020, Manny Rin was on a plane traveling home from Atlanta. He had just led a training for student leaders of the New Voters Project, preparing them to run voter registration drives for the upcoming election on campuses across the country.

Weeks later, Manny’s plans changed. The president had declared a state of emergency, and much of the country and nearly every college campus shut down. Interest in the November election was high, but nobody knew how fear of COVID-19, social distancing guidelines and shifting election rules would affect voter turnout, especially among younger voters.

As the election drew near, more than 5,000 students in 15 states took part — virtually — in the PIRG New Voters Project, contacting nearly 400,000 other students and urging them to get out and vote. This effort contributed to an eye-popping increase in young voter participation, with youth turnout up 22% over 2016 in New Jersey, 18% in Arizona, 17% in California and 14% in Georgia.

“Of course, some of 2020’s historic turnout can be attributed to expanded vote by mail options and increased interest in the election,” said Manny. “But this rise is also the culmination of years of our program investing in training young activists on college campuses and running a peer-to-peer voter engagement program at the local level.”

America’s largest nonpartisan young voter project

Voter registration drives had long been on the menu of public interest projects at Student PIRG chapters.

In 1984, these efforts scaled up in a big way. Doug Phelps, Susan Birmingham, Beth DeGrasse and other PIRG staff teamed up with Daniel Malarkey and other student leaders to organize a major conference on the student vote. They enlisted 880 campus leaders and newspaper editors to call on students across the country to attend a conference on student voter registration. Over the weekend of Feb. 11-13, 1,500 students from 42 states came to Harvard University to hear civil rights leader Jesse Jackson and other speakers, engage in workshops and conversations, and launch the National Student Campaign for Voter Registration.

That year, Jackson was also running for president. Given his campaign schedule, the civil rights leader admitted to the students he had hoped for a low turnout at the conference, so he could cancel and concentrate his energies on the Iowa caucuses.

“But here you are,” he said to a packed Memorial Hall while hundreds of others watched on closed-circuit TV because they couldn't fit inside the room. With a sly smile he added, “Something must be going on.”

Indeed, something was going on: Over the next eight-plus months, the campaign became the most successful student voter registration effort in the nation’s history, reaching 1,000 campuses and 2,000 communities, involving 10,000 volunteers, and helping 750,000 new young voters register (a 17% increase), while adding another 100,000 new registrations in predominantly low-income and minority communities.

Tactics evolve, the goal remains the same

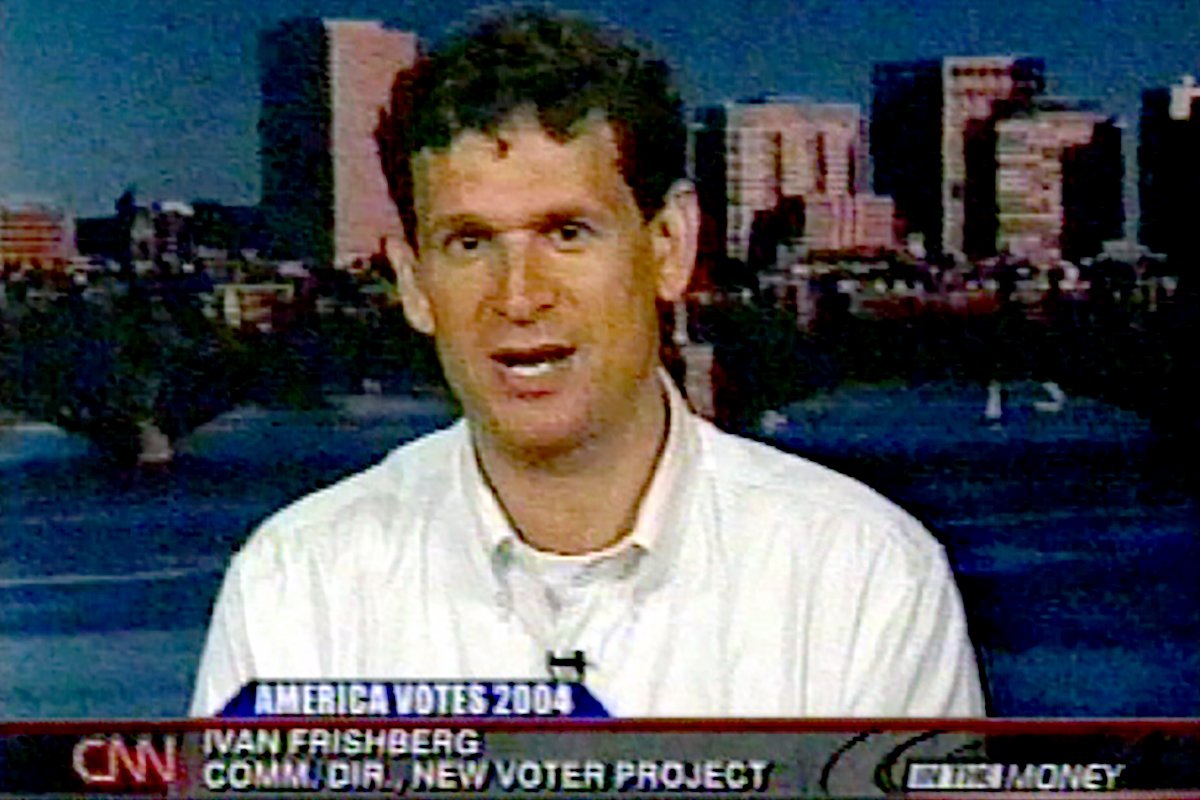

In 1994, the Student PIRGs teamed up with Rock the Vote!, United States Student Association, National Council of La Raza and others to form the Youth Vote coalition. In 2004, the Student PIRGs renamed NSCVR to become the (much pithier) New Voters Project and the project expanded thanks in part to a major grant by the Pew Charitable Trusts, secured under the leadership of PIRG’s Ivan Frishberg. As technology and students’ preferred modes of communication evolved, Manny Rin, Leigh-Anne Cole and other PIRG organizers incorporated social media, text and other types of peer-to-peer organizing, informed by sophisticated research conducted by partners such as the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE).

By 2020, the project had become America’s oldest and largest youth voter mobilization program, helping more than 2 million young people register and vote in elections spanning four decades.

Photo credit: CNN

Manny Rin, the director of Student PIRGs’ New Voters Project, trains new organizers. Photo by staff

Jesse Jackson is welcomed to speak to 1500 students at National Student Voter Registration Conference at Harvard, 1984. By staff

Ivan Frishberg leads the New Voters Project in 2004. Image from CNN news coverage.

Big money, big problems

More than two centuries after the United States was founded, the country still faces a daunting problem: How to provide every citizen an equal opportunity to make our voices heard and our votes count when elections are unduly influenced by the wealthy and wealthy interests?

A series of court decisions — including Buckley v. Valeo (1976), which struck down limits on political campaign spending; Citizens United v. FEC (2010), which struck down limits on corporate political contributions; and McCutcheon v. FEC (2014), which lifted certain limits on individual contributions — have narrowed the range of options for reform. In short, if you’re constrained in your ability to limit how much campaigns can spend, how much corporations can give, or how much individuals can give, how do you check the influence of monied interests over elections?

Where there’s a will, there’s a way

Enter the small donor matching fund. The idea is that even if you can’t cut big money down to size, you can still lift up the power of small donors — by matching the small contributions of ordinary people with public funds for candidates who refuse to take large or corporate contributions. In short, if a candidate can build enough support among people of average means, they still have a shot at raising enough money to compete in and win an election.

Emily Scarr, state director of Maryland PIRG, has been one of our most effective advocates for local small donor financing reforms.

In 2014, Emily and Maryland PIRG helped win unanimous passage of the Montgomery County Public Election Fund. Over the next four years, candidates for County Council and Executive lined up to qualify for the program, which requires candidates to reject all contributions over $150 and all corporate contributions in order to qualify for matching funds. Sure enough, in 2018 candidates participating in the program received nearly twice as many small contributions as their peers.

Over in Howard County, as a leader of the Fair Elections Maryland coalition, Maryland PIRG expanded support for a 2016 ballot measure to call on the County Council to establish its own small donor financing program. The measure passed, and the following July Howard became the second county in the state to officially establish a small donor election system.

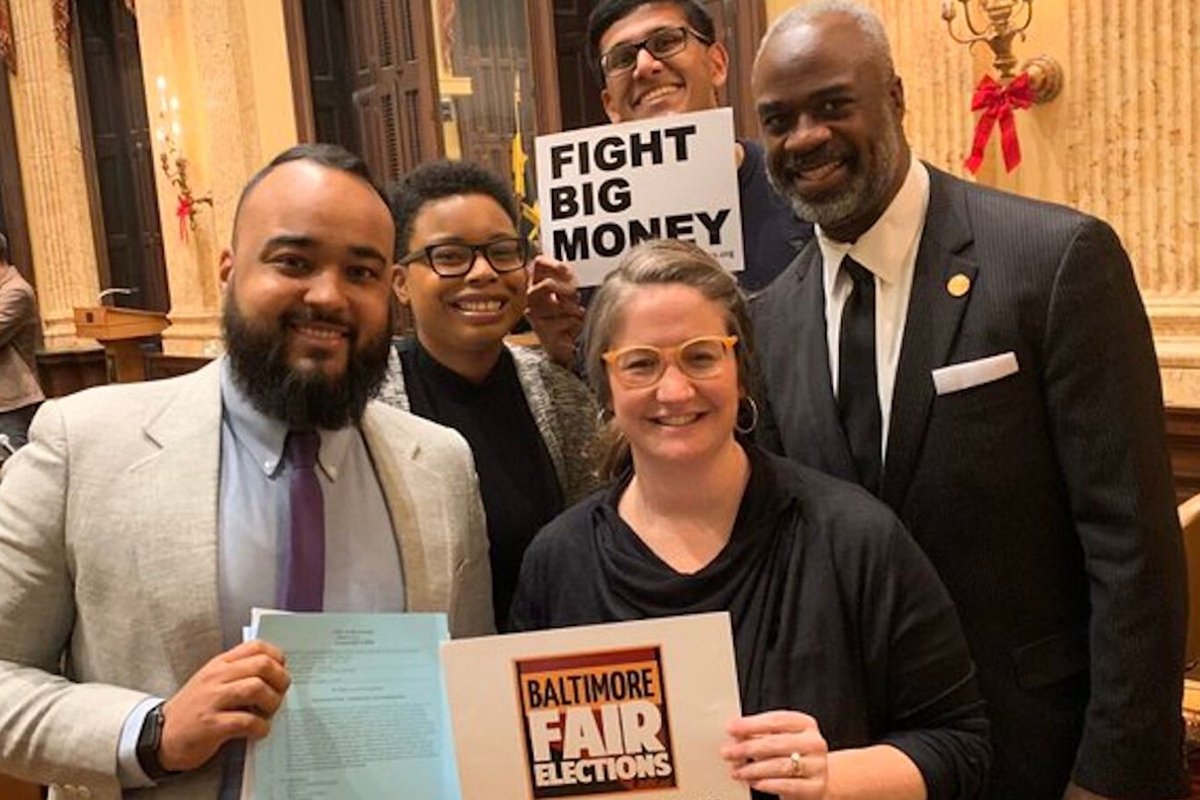

Emily and the Maryland team then led the 2019 effort to pass Baltimore’s Fair Election Fund. In 2021, the team helped win passage of a law updating and fully funding the small donor public campaign financing program for the state gubernatorial race.

Maryland PIRG has seen the greatest success in advocating small donor financing programs. But campaign finance reform advocates, including PIRG, have won similar reforms in New York City (and more recently New York State), Denver, Seattle and Maine.

Photo credit: Johnathan Comer

Maryland PIRG’s Emily Scarr speaks at a rally in June 2019. By Faith Carter

At Baltimore City Hall, Maryland PIRG Director Emily Scarr (front, right) and advocate Rishi Shah celebrate the Baltimore City Council’s passage of the Fair Election Fund with Councilman Kristerfer Burnett (front, left), who introduced the bill. Credit: staff

Illinois PIRG’s Abe Scarr spoke with reporters at the launch of our Democracy for the People campaign to empower small donors. Photo by Stefan Klapko Photography