Leaving dirty air in the past

An America where pollution is no longer the price of progress

A yellow fog

It was late October in 1948 when a yellow fog enveloped the city of Donora, Pennsylvania, about 30 miles south of Pittsburgh.

By Halloween, Donora residents were reporting difficulty breathing. The fog was so thick that a local doctor had to lead an ambulance by lantern on foot through the streets. Hundreds were admitted to local hospitals. Within days, 19 people from Donora and nearby Webster were dead. It was the worst air pollution disaster in U.S. history.

The pollution that killed these people was nothing new. In the early 20th century, Carnegie Steel and American Steel & Wire had factories in the area – and complaints about the smells, soot and gases emanating from their smokestacks mounted. But every day, most of Donora’s residents went to work in those factories. Their paychecks – and the political power of their bosses – kept any complaints in check. Until October 1948. As one resident wrote to Gov. James Duff, “I would not want men to lose their jobs, but your life is more precious than your job.”

* based on national air quality standards in place in 2016

* Pollutant information:

Carbon monoxide (linked to health damage), avg. concentration over 8 hour period.

Nitrogen dioxide (contributes to smog), avg. concentration over 1 hour period.

Ozone (contributes to smog), avg. concentration over 8 hour period.

Particulate matter (soot), 10 micron size avg. concentration over 24 hour period.

Sulfur dioxide (contributes to acid rain), avg. concentration over 1 hour period

Intolerable

It took too long, but the tragedy in Donora – combined with similar incidents in Los Angeles, New York City and elsewhere; new efforts in public health research; action by forward-thinking elected officials; and public education and advocacy by environmentalists and health advocates – ultimately helped transform the way Americans view pollution.

No longer was the smoke and soot that accompanied industry the price we paid for progress. They were problems we should no longer tolerate in a country that had the resources and the wherewithal to solve them.

For the past five decades, PIRG members and staff have built on this legacy – by strengthening the federal Clean Air Act, rebuffing attempts to weaken clean air protections, winning state action on clean air, and more.

Video credit: Rick Ray via Shutterstock

Sweeping impact, rare support

On Nov. 15, 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed into law a new and improved federal Clean Air Act that would, in the decades to come, make an enormous positive impact on the quality of the air we breathe. Almost as remarkable from today’s perspective, the law also enjoyed a wide swath of bipartisan support.

U.S. PIRG and the state PIRGs contributed to both the strength of the clean air provisions and the bill’s broad support.

The 1990 Clean Air Act amendments strengthened the law’s enforcement and addressed four specific problems: acid rain, urban air pollution, toxic air emissions and stratospheric ozone depletion. In just a few decades, the results would become clear as day:

Carbon monoxide pollution plummeted by more than 75%

Nitrogen dioxide levels went down at least 50%

Particulate pollution levels dropped at least 40%

Toxic pollutants such as benzene and mercury declined more than two-thirds

Lead levels in outdoor air decreased more than 99%.

One of the main causes of acid rain, sulfur dioxide pollution from power plants, declined more than 80%

Far more importantly, these numbers translated into lives saved and health improved. Together, the original Clean Air Act and the 1990 amendments would go on to help prevent 400,000 premature deaths and hundreds of millions of cases of respiratory and cardiovascular disease. Between 1990 and 2010, deaths from air pollution in the U.S. dropped nearly 50%.

Clean air and health came first

The changes to the law that made these results possible were the subject of heated political debate. Champions of a stronger Clean Air Act, such as U.S. Reps. Henry Waxman (Calif.) and Gerry Sikorski (Minn.), negotiated the law’s final provisions with other members of Congress, the White House, industry lobbyists and environmental advocates. As they did so, Gene Karpinski and other PIRG staff persistently reminded all parties to put clean air and public health first.

In October 1990, for example, Gene held congressional feet to the fire when officials agreed to water down some elements of the amendment, telling a New York Times reporter, “The clean air bill went into the back rooms and it looks like a dirty air bill is coming out.”

Our advocacy was also bolstered by our action and progress at the state level, including on acid rain. Back in the 1980s, acid rain was stripping some forests bare and leaving many lakes and rivers lifeless. In response, in 1982 Minnesota PIRG spearheaded passage of the Acid Deposition Act, the nation’s first law targeting acid rain. In 1985 Massachusetts lawmakers enacted the Acid Rain Cap-and-Cut Law, after MASSPIRG gathered enough voter signatures to qualify the issue for the statewide ballot. These state laws provided blueprints for the 1990 federal provisions on acid rain, which capped sulfur dioxide emissions and allowed industries to trade emission cut credits.

Near 90% majorities in Senate and House

Despite the usual jockeying for partisan advantage during the bill’s advance through Congress, the floor votes in the U.S. Senate and House were overwhelming: 89 to 11 in the Senate and 401 to 21 in the House.

The lopsided votes were attributable to multiple factors including:

a public outpouring of support and action on the environment that accompanied the 20th anniversary of Earth Day in April 1990,

a level of partisan competition that seems quaint by today’s standards, and

hundreds of thousands of petition signatures, postcards, letters, letters to the editor, and phone calls (all of this in the pre-digital age, mind you), mobilized in large part by PIRG Student chapters, PIRG canvassers and PIRG organizers.

In the end, the vote came down to a simple calculation for senators and representatives of both parties. As Sen. Mitch McConnell (Ky.) summed it up, “I had to choose between cleaner air and the status quo. I chose cleaner air.”

Photo: tmpr via Shutterstock

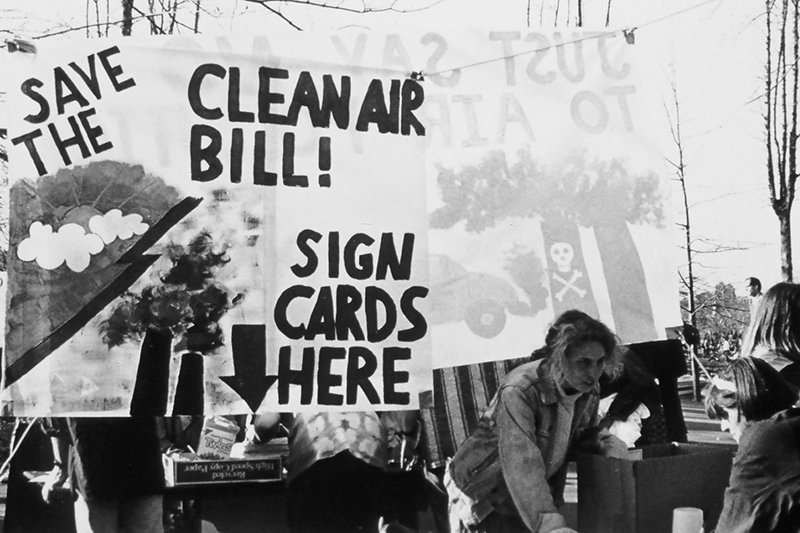

PIRGs gather 500,000 petition signatures in support of the Clean Air Act in 1990. Photo by staff.

PIRG’s Jenny Carter and Rick Hind meet with Rep. Joe Moakley about air quality in 1990. Photo by staff.

Rep. Henry Waxman, flanked by PIRG staff, presents postcards calling for a strengthened Clean Air Act in 1989. Standing behind Rep. Waxman are Beth Zilbert, MOPIRG director; Andy Buchsmaum, PIRGIM advocate; Jim Leahy, ConnPIRG director. Photo by staff.

‘Corrections days’

On March 23, 1995, Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich announced his plan to establish procedures for identifying “the dumbest things the federal government is currently doing” so Congress could “just abolish them.” He called them “corrections days.”

Not a terrible idea on the face of it.

But the speaker’s targets included such “dumb” things as clean air protections, as well as clean water safeguards, toxic waste cleanups and asbestos removal.

At an event with Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Carol Browner, Speaker Gingrich called the EPA the government’s “biggest job-killing agency.” As an alternative, he envisioned businesses, not the EPA, taking the initiative on clean air and other issues.

The speaker’s majority whip, Rep. Tom DeLay (Tex.) was even more extreme, referring to the EPA as the “Gestapo” and pledging to rescind the 1990 Clean Air Act amendments that his fellow Texan, George H.W. Bush, signed into law (and which PIRG campaigned vigorously for).

1.2 million Americans objected

The attacks on clean air and environmental protections at first flew under the radar. After all, the Republican Party had not enjoyed a majority in the U.S. House since 1952. Gingrich’s Republican Revolution was big news.

At doorsteps, on college campuses, on the phone and elsewhere, PIRG organizers and our allies began to raise awareness of the urgency of stopping the rollback of America’s environmental protections.

During the weekend of February 24-26, a thousand students came together at the University of Pennsylvania for the Free the Planet conference. It was “thrilling to see over 1,000 students from 35 states speak out for the environment,” said Pete Maysmith, then field director for U.S. PIRG. “Now is the time to act to save the environment and these are the people who will do it.”

Many of those students became PIRG canvassers that summer, gathering petition signatures demanding that Congress stop its efforts to roll back 25 years of environmental progress.

On Nov. 1, our coalition delivered 1.2 million signatures to Congress. U.S. PIRG’s Karpinski told the Associated Press, “These are the most signatures gathered on environmental issues in the history of the environmental movement.”

Defense when necessary

For the most part, the nation’s bedrock environmental protections were left unscathed by the speaker’s “corrections” and other attacks. By 1996, Speaker Gingrich had shifted his rhetoric, calling for a “new environmentalism” based on sound science.

Meanwhile, the Stop the Rollbacks campaign solidified PIRG’s reputation on the national stage as a group that delivers what we promise – including the largest share of the 1.2 million signatures gathered by a single group within the environmental coalition.

More importantly, the experiences gained and lessons learned in the Stop the Rollbacks campaign provided a strong foundation for subsequent efforts to thwart attacks on our environmental protections during the George W. Bush administration and the Trump administration. The price of environmental protection, to paraphrase Jefferson, is constant vigilance. PIRG, together with our environmental allies and, as of 2008, our partners at Environment America, remains on watch.

Photo: On Nov. 1, our coalition delivered 1.2 million signatures to Congress. U.S. PIRG’s Karpinski told the Associated Press, “These are the most signatures gathered on environmental issues in the history of the environmental movement.” Credit: staff photo

PIRG’s Derek Cressman and Carrie Doyle organizing the Free the Planet Conference in 1995. Photo by staff.

Dan Jacobson speaks on behalf of Florida PIRG at a Free the Planet program in Florida. Photo by staff.

Environment America's Christy Leavitt speaks at a rally to defend clean air laws in 2009. Photo by staff.

States raise the bar

Even when clean air protections have come under attack at the federal level, PIRG has advocated and won stronger limits on air pollution in states around the country, as exemplified through three alliterative campaigns in Massachusetts (to clean up the Filthy Five), Connecticut (the Sooty Six) and Pennsylvania (the Toxic Ten).

Massachusetts cleans up the ‘Filthy Five’

The Clean Air Act has saved hundreds of thousands of lives, but the act has had what PIRG advocates called a “lethal loophole”: Older, “grandfathered-in” power plants were free to emit higher amounts of soot, mercury and other pollutants, and remained one of the nation’s largest sources of health-threatening air pollution.

MASSPIRG termed five of the dirtiest power plants in Massachusetts the “Filthy Five.” In 1998, PIRG advocates set out to rein in their pollution.

After MASSPIRG Legislative Director Rob Sargent discovered an obscure law permitting anyone to petition any state agency to adopt a restriction, we filed a petition that would limit these plants’ pollution.

All eyes turned to acting-Gov. Paul Cellucci, then running for election. Weighing his odds against a PIRG-backed petition, Cellucci agreed to clean up the plants.

For two years, MASSPIRG worked to hold the state to that promise, releasing research reports, negotiating with power plants, and turning out 1,000 people at public hearings.

On April 23, 2001, we won: Massachusetts finalized the first-ever state-imposed limits on power plant emissions of mercury and carbon dioxide.

Connecticut tames the ‘Sooty Six’

Soot pollution is linked with acid rain, respiratory disease and premature death. In 1997, ConnPIRG launched a campaign to clean up six of Connecticut’s worst polluters: the “Sooty Six.”

Working on behalf of ConnPIRG, Green Corps campaigners Bernadette Del Chiaro and Merc Pittinos went door to door to build support for a bill targeting the Sooty Six.

Canvassers educated 36,000 Connecticut citizens on power plants, thousands of whom wrote letters urging the governor to clean up the plants.

Year after year, the campaign built support but fell short, inspiring a campaign slogan: “If we lose, we lose big and come back stronger.”

After three years of grassroots organizing, Connecticut residents were on our side. One citizen, Bob Megna, felt so moved by our campaign that he ran for — and won — a seat in the state Legislature after his representative had opposed cleaning up the Sooty Six.

We had shifted the political winds, and in May 2002, Gov. John Rowland signed the first law in the country to limit power plant carbon pollution.

Pennsylvania tackles the ‘Toxic Ten’

The Pittsburgh region ranks in the top 2% of counties with the highest cancer risk from air pollution. In 2019, the worst polluting facilities, dubbed the “Toxic Ten” by PennEnvironment, accounted for 60% of Allegheny County’s emissions from industrial sources.

Since 2015, PennEnvironment has released updated lists of these 10 worst polluters and hosted an action week inviting Pittsburghers to call for stronger pollution restrictions.

In 2021, Pittsburgh saw progress. After reducing its emissions, the No. 1 polluter in years past dropped to the No. 7 slot, and for the first time, another Toxic Ten polluter dropped out of the ranking altogether.

PennEnvironment members and staff are hoping for more positive results in the years to come, results similar to those won in:

Connecticut, where our action helped cut emissions from the Sooty Six by a whopping 86%,

Colorado, where the CoPIRG-backed Colorado Clean Air Act of 1992 has diminished Denver’s infamous “Brown Cloud,” and

Massachusetts, where by 2017, all of the Filthy Five power plants had agreed to shut down – and a solar farm had sprouted atop the retired coal plant in Holyoke.

Photo credit: staff

MASSPIRG activists demonstrate opposition to Massachusetts’s Filthy Five power plants' pollution. Photo by staff

Toxics Action Center’s Bernadette Del Chiaro and Alyssa Schuren stand with Connecticut residents who worked on the Sooty Six campaign. By staff

PennEnvironment’s Ashleigh Deemer. By Adam M. Wilson Photography